SOOC

Fifth Call: Bird of Many Colors

Yesterday, I wrote about Jessica being my own personal contemplation trigger. Today, I’d like to explore at least one of the thoughts she put into my head.

First and foremost: I’ve discovered that Jessica and I (seem to, at least) approach art/photography in completely different manners. Jessica, please correct me if I’m wrong, but you — apparently — get an image in your mind and do your darnedest to make it a reality. Because this image in your mind is very concrete, you want as much control as possible over any variable that plays a role in the creation of your art.

I, on the other hand, start with the vaguest of notions and see where they take me. I neither want nor need control over the variables, because I’m happy to let circumstances beyond my control (I don’t know if this is a terribly accurate descriptor) lead me to my destination.

I don’t shoot in RAW. (There I admitted it: I’m a Philistine!) I’ve simply never felt the need nor had the desire (and I’ve never bothered to install my camera’s software onto my computer). I own an Olympus E-5, because I’ve always been incredibly impressed with the JPEGs produced in an Olympus camera. (Its color saturation stands out in my mind.)

I take a lot of photos. On average, I shoot 100 pictures a day. I imagine this seems excessive to some. (You, Jessica?) Because I begin with vague notions, though, I try to produce as much raw material as possible, and then see what rises to the top and how it inspires a finished product.

I’m perfectly content to let the software developers at Olympus make decisions for me (with their algorithms), because I tend to get paralyzed by seemingly endless options. If the field is wide open, I don’t know where to begin.

When I’m creating a painting or a drawing or an art journal page (even when I’m writing a blog post or a story), I give myself parameters, and these allow me to start. Waiting until I have an image completely worked out in my mind before even picking up my camera (or a paintbrush or a pencil or a keyboard) is almost the same as packing it into the box it came in and placing it on my closet shelf. My universe of creating art is very much governed by the law of physics that states, “A body in rest tends to stay at rest, and a body in motion tends to stay in motion, unless the body is compelled to change its state.”

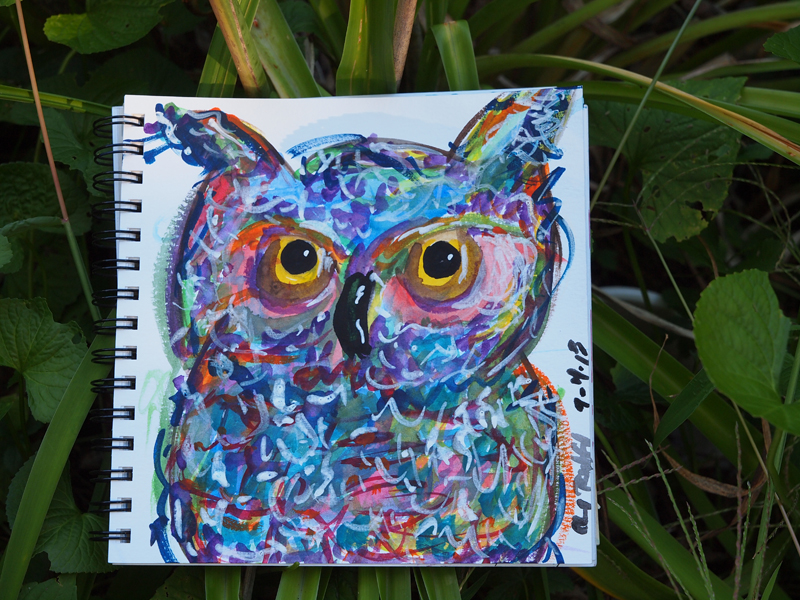

My owl painting was inspired by (the much better) work of artist Dean Crouser. His paintings were my starting point, and my parameters included the watercolor paints that I own, the paper I could lay my hands on, the amount of time I had to devote to the painting (not much), and my skill level. While I’m relatively happy with my finished product, it looks nothing like the notion I started with. But that’s perfectly fine. The freedom I found in creating this painting and the willingness to simply follow my own intuition makes me want to frame it.

What I’ve learned through this week’s project is that “straight out of the camera” is a distraction. NO, wait. I’ll go further and say that it is meaningless. (Now, I have to decide if I’ll delete ALL the SOOC tags attached to my photos on Flickr — nah, probably not). But this rather bold statement does not mean that the conversation has nowhere else to go. On the contrary, I’d like to offer food for further (very likely tangential) thought.

H.W. Janson, in The History of Art, writes: “We must remember that any image is a separate and self-contained reality which has its own ends and responds to its own imperatives, for the artist is bound only to his creativity.”

Just let that rattle around in your brain for a little while.

Janson dedicates the introduction of The History of Art to answering the question, “What is art?” and often refers to a work by Picasso called Bull’s Head:

… we might say that a work of art is a tangible thing shaped by human hands. … Now let us look at the striking Bull’s Head by Picasso …, which consists of nothing but the seat and handlebars of an old bicycle. How meaningful is our formula here? Of course the materials used by Picasso are man-made, but it would be absurd to insist that Picasso must share the credit with the manufacturer, since the seat and handlebars in themselves are not works of art.

So, according to Janson, Picasso doesn’t have to acknowledge Huffy or Raleigh or whoever made the bicycle parts he used in his sculpture. Do I have to acknowledge Pelikan for the paints I used in my owl portrait, since I didn’t grind the pigments or mix them myself? If I shoot in JPEG instead of RAW, do I have to acknowledge the the software developers at Olympus?

Janson again:

… even the most painstaking piece of craft does not deserve to be called a work of art unless it involves a leap of the imagination. But if this is true are we not forced to conclude that the real making of the Bull’s Head took place in the artist’s mind? No, that is not so, either. Suppose that, instead of actually putting the two pieces together and showing them to us, Picasso merely told us, “You know, today I saw a bicycle seat and handlebars that looked just like a bull’s head to me.”

This makes me ask: if I don’t know what I’m going to create when I start creating it, am I not an artist?

One more, this time from Madeleine L’Engle in Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art:

In my commonplace book I’ve copied down the words of a Hawaiian Christian, Mother Alice Kaholsuna:

“Before the missionaries came, my people used to sit outside their temples for a long time meditating and preparing themselves before entering. Then they would virtually creep to the altar to offer their petition and afterwards would again sit a long time outside, this time to ‘breathe life’ into their prayers. The Christians, when they came, just showed up, uttered a few sentences, said Amen and were done. For that reason my people called them haloes, ‘without breath,’ or those who failed to breathe life into their prayers.”

Her description of prayer is a beautiful description of the creative process. Meditation, silence, faith in that which we cannot control or manipulate. And letting go of that dictator self which constantly tries to take over the controls. And listening.

Question: if I give up control by not shooting in RAW am I serving the work? If I don’t fully form an image in my mind before starting to create it, am I not breathing life into it?

OK, I lied. I have one more quote (from L’Engle again): “Picasso says that an artist paints not to ask a question, but because he has found something, and he wants to share — he cannot help it — what he has found.”

I don’t know if I’ve ever come across a more concise description of what has motivated me all my life: “he wants to share — he cannot help it — what he has found.” SOOC or post-processed; RAW or JPEG; concrete image or vague notion: does any of it matter, if all I want to do is share?